When my son John was in third grade he briefly glommed on to my collection of old Hardy Boys story books. We’d read them together at bedtime as I tried to instill in John a love for the Boys, their pals (“chums,” to be precise) and their ancient (to him) adventures. Alas, Harry Potter soon distracted him and the Hardy Boys went back to gathering dust.

For those of you too young to remember (or too Nancy Drew-ish in your literary tastes to care), The Hardy Boys was a 58-book series that ran from 1927 to 1979, coinciding with the sweet spot of my 1950s and ’60s childhood. (The success of the books also spawned a black-and-white Disney TV serial in the ’50s, a Saturday morning cartoon from 1969-71, and the truly awful Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, which ran from 1977-79.)* Long story short, The Hardy Boys books described the sleuthing adventures of Frank and Joe Hardy, sons of the famous private investigator Fenton Hardy, in sometimes excruciating prose.

Frank and Joe evolved over the books and years from cynical, in-it-for-the-money 1920s teenagers to paragons of 1950s authority-respecting American youth. A Hardy sidekick, Chet Morton, evolved in somewhat different fashion, which brings me to today’s topic: Parents of overweight and obese kids are getting really bad at telling that their kids have a weight problem.

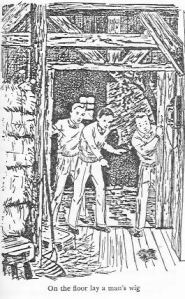

Chet was the clumsy, jalopy-driving foil to Frank and Joe’s buff manliness. In the very first book, “The Tower Treasure,” Chet is described thusly: “He was a plump boy who loved to eat and was rarely without an apple or a pocket of cookies.”** This puzzled John, who looked at the accompanying drawing and said, “Why do they call him plump? He looks pretty skinny to me.” He had a point. As you can see, Chet may have had a roundish face and a bit of fullness to his arms, but his waistline and legs are as skinny as Frank and Joe’s. “I guess that was considered fat back in those days,” I explained to John with a shrug. Then I looked it up and found that only about 2% of children were obese in the 1930s. By the time we were reading this in ~ 1999, about 15% of children were obese. By 2012, 21% of American teens were obese. It was true: back in the 1930s, an artistic bit of a double chin or a pinch of chub at the belt line was all it took to portray a kid who liked to keep his pockets lined with cookies.

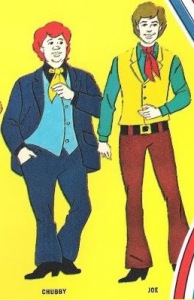

Chet’s evolution over time says a lot about how we perceive child obesity. As time went on and obesity rates rose, his Jazz Era chubbiness wasn’t enough. Chet got fleshier. By the time the late ’60s cartoon appeared, Chet (renamed “Chubby,” in case kids zoned out on Sugar Smacks didn’t get the point) had taken on a doughy, full-figured form that signaled to contemporary viewers that Chet was, well, chubby. Today, when more than 1/3 of adults are considered to be obese, it’s getting harder to send that signal: portrayals of characters as truly “fat” have kind of gone over the top, and they’re usually pretty cruel.

A new study in the journal Child Obesity shows how society’s idea of “normal” weight has changed since the Depression. In a survey of parents of 2-5 year-olds, 94.9% of parents whose child was in the “overweight” category, and 78.4% of those who were frankly obese said that their child’s weight was “just about right.” As our kids get heavier, our “parent goggles” simply adjust. In a strange corollary, I talk to parents all the time who worry that their average-build kids are too skinny.

The sorta-good news? Parents’ mis-perception of their overweight children actually improved somewhat from a similar study done 20 years earlier.

Given all that, I wonder how Mr. and Mrs. Morton viewed their cookie-pocketed boy who got steadily heavier over the years but, strangely, never aged? Alas, in 58 books, they never said a word…

* * *

* Shaun Cassidy as Joe Hardy?? Spare me…

** Chet was also described at various times as “big boy,” fat, plump, chubby, stout, heavy-set, chunky, “the chubby one,” portly and round. (“Portly” was my favorite.)