One of the biggest difficulties in proving a causal link between cesarean birth and chronic health problems in childhood is the type of research studies that can practically and ethically be done during pregnancy.

One of the biggest difficulties in proving a causal link between cesarean birth and chronic health problems in childhood is the type of research studies that can practically and ethically be done during pregnancy.

The gold standard in medical research is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). In an RCT researchers randomly place subjects into either “treatment” or “control” groups, then expose the treatment group to something—a new vaccine for Infection X, for example—and then compare outcomes in the two groups later on. (In this example, how many kids in the treatment [vaccinated] group came down with Infection X versus how many in the unvaccinated control group?) If there’s a significant difference in outcomes between the two groups, you’ve got a strong argument that the treatment made the difference.

As you can imagine, randomly assigning pregnant women to cesarean (treatment) or vaginal birth (control) groups is nigh onto impossible—ergo, you can’t do an RCT. This means that virtually all research studies on the issue of cesareans and chronic childhood have been observational in nature—looking backward in time at databases, for example, or trying to fish significant trends out of hospital registries, birth cohorts and the like. The best an observational study can tell you is that A and B are associated with one another, but that’s it—you can’t prove that A actually causes B. An observational study can’t prove that cesareans are a cause of asthma; it can only say that cesareans are associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma.*

So mode-of-delivery RCTs are out of the question…or are they? Actually, in 2004, a Canadian research team did one.

The multi-center, multi-nation Term Breech Trial wasn’t about whether cesareans might increase the risk of childhood asthma, diabetes and such. It was about trying to figure out whether elective cesarean section or vaginal birth was the safest way to deliver a breech baby at term. Since the existing research was somewhat murky at the time, it was considered ethical (with informed consent) to randomize women to have either a planned cesarean or attempt a vaginal birth.

The particulars of the breech birth debate are best left for another post, but tucked away in the study’s results section was this little nugget:

“…more parents in the planned cesarean birth group than the planned vaginal birth group reported that their children had had medical problems in the past several months…relative risk, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.05-1.89; P=0.2.”

Plain English version (mine): The toddlers who had been in the planned cesarean group were about 40% more likely to have been sick in the previous few months than those in the planned vaginal birth group. The types of medical problems—typical 2 year-old stuff like colds, ear infections and stomach flu—were no different between the groups. The only difference was in the numbers of children who’d gotten sick.

As is the case with all medical research, you can find things in the study to complain about: relatively small numbers, for example, the use of parental questionnaires and the fact that some mothers in planned vaginal birth group ended up having cesareans (and vice-versa), etc.

But here’s my bottom line:

In a randomized trial of pretty well-matched subjects, those babies whose mothers were in the planned cesarean group tended to get sick more often than those in the planned vaginal birth group.

This doesn’t address the issue of chronic illnesses like asthma, type 1 diabetes and the like, but it does support the theory that cesarean birth can mess with a baby’s developing immune system.

* * *

*Here’s an exaggerated example of the trouble with mistaking association for causation: Virtually all adults who die suddenly of heart attacks drank water in the 24 hours before they died. So, drinking water is associated (time-wise) with heart attacks. But you would be wayyyy wrong to say that, based on that association, a glass of water can cause a heart attack.

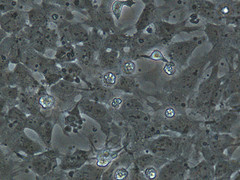

**Credit: SUNY Downstate Medical Center