“Who even does early cord clamping anymore?”

“Who even does early cord clamping anymore?”

This question was raised recently by a young doctor at the family medicine residency program where I teach. She and her residency colleagues had been taught in their OB rotation that delayed cord clamping is the childbirth standard of care. The benefits are proven, the resident said, and early clamping doesn’t do anything for anybody.

“So why would anyone do it?”

Good question. Yet judging from the emails I received after my last post, DCC is far from the standard of care around the country:

-

An East Coast doula wrote that her clients can have DCC performed at birth “if they request it.” (If they request it?? That’s a bit like saying, “There’s this thing called oxygen, and if it looks like your baby’s at risk of brain damage from a lack of it, we can give him some. If you ask us to, that is.”)

-

A California midwife wrote that the obstetricians at her hospital are adamant that DCC is “too risky” for newborns. Despite the evidence she presented to them, they’re sticking with ECC.

-

A Midwestern family physician reported that the DCC/ECC debate has split the medical staff where she practices. Although there’s some overlap, the family docs are largely pro-DCC, while the OB staff is in favor of ECC.

Clinging to interventions that have been shown to be useless and even harmful is, unfortunately, nothing new in the history of medicine.

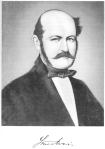

Perhaps the most infamous example in the maternity care world is that of Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), a Hungarian-Austrian obstetrician who clearly demonstrated that simple handwashing could greatly reduce maternal deaths from puerperal fever—a virulent infection that plagued crowded maternity wards in the 19th century. Everybody ignored him, his career crashed, and he died in an asylum…and a few decades later everyone was washing their hands. (A brief synopsis of his story is attached below, excerpted from my book, Birth Day: A Pediatrician Explores the Science, the History, and the Wonder of Childbirth.)*

I’m encouraged that the young doctors I work with see DCC as a no-brainer (or a pro-brainer, if you’ll pardon the pun.) But too many doctors don’t see the timing of cord clamping as the important issue it is. For them, it will probably take the Invisible Hand of the Market, in the form of pressure from pregnant clients, to change minds and practices, if not hearts.

So tell me, what’s the DCC/ECC environment where you live? Email me or (better still) add a comment on the blog!

* * *

*(Shameless self-promotion: Birth Day—a ripping good yarn—is available in paperback or Kindle from Amazon, or you can order it from me directly at www.marksloanmd.com).

Excerpt from Birth Day: A Pediatrician Explores the Science, the History, and the Wonder of Childbirth (Copyright 2009, Mark Sloan M.D.)

“In 1844, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis, an assistant lecturer in the First Obstetric Division of the Vienna Lying-in Hospital, began to make the same connection [as Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes]. Semmelweis noticed that women who gave birth in his First Division, which was staffed by doctors and medical students, had eight times the risk of contracting puerperal fever than those who were delivered by midwives in a distant part of the hospital. Of the many differences in patient care between the two divisions, Semmelweis saw one that stood out. Doctors did autopsies on women who had died of puerperal fever. Midwives did not.

With no access to Holmes’s still obscure paper, it took three years and a number of failed hypotheses for Semmelweis to put it all together. The final piece of the puzzle fell into place when, like Holmes, he was struck by the similarities between puerperal fever and the death of a colleague from an infection incurred during an autopsy. “Suddenly a thought crossed my mind,” he wrote. “The fingers and hands of students and doctors, soiled by recent dissections, carry those death-dealing cadavers’ poisons into the genital organs of women in childbirth.”

Semmelweis immediately ordered all doctors and students in the First Division to wash their hands in a chlorinated lime solution before attending to patients. The results were startling: mortality rates from puerperal fever fell from 18 percent in the first half of 1847 to less than 3 percent by that November. But like Holmes’s in America, Semmelweis’s breakthrough was dismissed by his colleagues, including Friedrich Scanzoni, the most prominent obstetrician in Vienna.

Semmelweis’s discovery ultimately led to the ruin of his own career and health. He was dismissed from the Vienna Lying-in Hospital in 1849, in large part because of his increasingly strident arguments with colleagues. Despondent, he spent a few unproductive years at a hospital in his native Hungary before returning to Vienna. There he wrote articles and letters blasting his former colleagues. He even accused them of murder, calling them, among other things, “medical Neros” for ignoring his advice while women died. Disabled by severe depression, Semmelweis died in a mental hospital in 1865—ironically, from an infection that started in a cut on his finger.”